by François Lopez

Abstract

This Research Note examines why some terrorist organisations, which depend on the “oxygen of publicity” provided by the news media, would target journalists. Journalists have long been the targets of attacks by terrorist organisations and this Research Note analyses why this has been the case by focusing on two case studies of one ‘old’ and one ‘new’ terrorist organisation; ETA and IS respectively. The research is centred around three hypotheses: (i) terrorist groups target journalists for collaborating with ‘the enemy’; (ii) terrorist groups target journalists in response to ‘negative’ portrayal and reporting in the media; and,(iii) new terrorist organisations do not require the ‘oxygen of publicity’ provided by the news media since they can count on the Internet and social media to serve this purpose. The findings suggest that hypotheses (i) and (ii) can be confirmed while hypothesis (iii) can be partly confirmed. The findings also reveal that the distinction between ‘old’ and ‘new’ terrorism can be questioned when examining the rationales of both terrorist organisations for killing journalists.

Keywords: media; terrorism; journalism; Islamic State (IS); ETA; propaganda.

Introduction

Speaking in front of representatives of the American Bar Association at the Albert Hall in the UK in July 1985, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher warned that the news media was playing into the hands of terrorists. Attracted by the violence and the atrocities of terrorists attacks, Thatcher claimed, the news media was providing “the oxygen of publicity” on which terrorist organisations depend.[1]

The problematic relationship between journalists and terrorist organisations has been labelled a ‘symbiosis’ by some academics.[2] On the one hand, terrorist organisations depend on the multiplier effects of the media to spread fear or draw attention to their cause. They follow a ‘propaganda by the deed’ strategy, which allows relatively small-scale acts of violence to be witnessed by very large audiences.[3] As Walter Laqueur put it, “publicity is all” for the terrorist.[4] On the other hand, the news media also profit from the human drama, individual grief, personal tragedy, and collective panic which terrorism provides and which guarantees mass audiences. The news media thrives on the television-like ‘entertainment’ and real-life drama provided by terrorist attacks.[5] Terrorist organisation therefore count on the media for publicity, while the news media benefits from terrorist organisations’ ability to create fear which can be sold to anxious readers, listeners, and viewers.

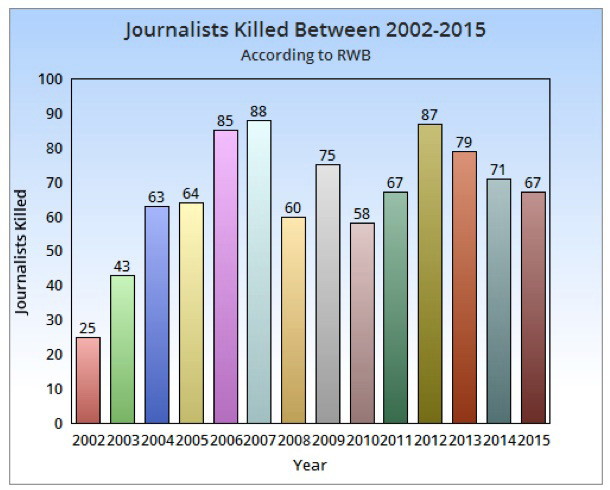

Despite the apparent symbiosis between terrorism and journalism, terrorist groups have actively targeted their source of publicity. Attacks on journalists by terrorists have been on the increase in recent years.[6] The following graph, based on research by Reporters Without Borders, reveals that 932 journalists were killed between 2002 and the end of 2015.[7]

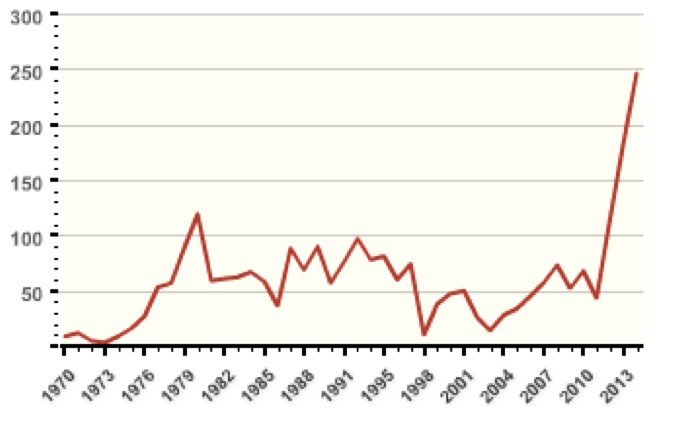

The Global Terrorism Database (GTD) of START at the University of Maryland - which has recorded attacks by terrorist groups from 1970 onwards - demonstrates that attacks on journalists by terrorists are not a new phenomenon.[8]

However, the graph also reveals that since 2011 there has been a dramatic increase in the number and frequency of attacks on members of the news media by terrorist organisations. This Research Note summarises the findings of a Master’s Thesis which sought to answer the research question: Why would terrorist organisations, which depend on the “oxygen of publicity” provided by the news media, target journalists?

Theoretical Framework and Methodology

Taking into account the distinction between ‘old’ and ‘new’ terrorist organisations [9], the thesis examined one case study of an old terrorist organisation–Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (Basque Homeland and Liberty) or ETA–and a new terrorist organisation–ad-Dawlah al-Islāmiyah fīl-Irāq wash-Shām, better known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria or IS.

Two theories were chosen to guide the research, namely rational choice theory and communication theory. The former suggests that terrorist organisations are rational actors and use terrorism to achieve political ends, aiming to influence the behaviour of governments through their actions.[10] The latter suggests that terrorism is an act of communication aiming to send out a message to a specific audience.[11] By using terrorism as an act of communication, terrorist organisations implement the strategy of ‘propaganda by the deed’ to attract the news media, which will in turn disseminate their message.[12]

Together, the theories suggest the following:

Terrorists are rational actors and their actions are strategic;

Terrorists aim to modify the behaviour of opponents through violence;

Terrorists want to send out a specific message to a specific audience through violence-generated publicity.

The thesis aimed to answer the research question through document analyses. In the case of ETA, open-source documents such as press releases, statements, and official documents of the organisation were selected. Regarding IS, open-source statements published on social media, the organisation’s English-language magazine Dabiq, and reports by non-governmental organisations and news media outlets were chosen. Three hypotheses were devised to answer the research question:

Hypothesis One: Terrorist groups target journalists for collaborating with ‘the enemy’.

Hypothesis Two: Terrorist groups target journalists in response to ‘negative’ portrayal and reporting in the media.

Hypothesis Three: New terrorist organisations do not require the ‘oxygen of publicity’ provided by the news media since they can count on the Internet and social media to serve this purpose.

Findings of the Research

Hypothesis One

The findings revealed that both ETA and IS targeted journalists for collaborating with the enemy. The news media were regularly portrayed by ETA as collaborators of an oppressive Spanish state, and journalists accused of being “traitors” or “accomplices of the oppressors of the Basque Country”.[13] The news media was included in what a former ETA leader defined as the Spanish state’s apparatus of domination–the government, the education system, the economy, and the mass media.[14] ETA portrayed the news media as “an effective instrument of war against Basque resistance” [15], and accused journalists of being “at the forefront of the Interior Ministry’s campaigns (…) to prolong the conflict permanently” and “to impose their Spanish project through force”.[16]

IS is convinced that the Western news media and its local “allies” are engaged in a media and “propaganda war” [17], launched by Western journalists representing “media opposition to the Islamic State from the coalition of the cross”.[18] It claims that it is facing “a media and military campaign” from the Western world.[19] In October 2015, Reporters Without Borders published a report on the “major persecution campaign targeting all types of media workers” by IS in Mosul, revealing that IS was actively arresting and killing journalists for leaking information as well as for “treason and espionage”.[20] International Media Support reported that “IS treats all journalists as ‘enemies’ or potential traitors collaborating with the enemy”.[21] Unfortunately, sufficient evidence in IS’s English language documents to support this hypothesis was lacking. The author of this Research Note was unable to find additional evidence in English. Research regarding this hypothesis was also limited due to lacking language skills in Arabic. Nevertheless, it appears from the above that there is some evidence to support this hypothesis for IS as well.

Hypothesis Two

The findings based on the study of documents revealed that both ETA and IS target journalists in response to ‘negative’ portrayal and reporting in the media. Jose Maria Portell was the first journalist to be targeted and killed by ETA, right amidst Spain’s transition process from Francoism to democracy. ETA released a statement following his death, stating that J.M. Portell had been “a specialist in intoxication” and charging him of “using his prestigious career, as well as his privileged methods, to discredit, calumniate, and ultimately attack ETA”.[22] In 1995, an internal document originating from the Koordinadora Abertzale Sozialista, the Socialist Patriotic Coordinator (KAS) [23], entitled ‘Txinurriak’ or Basque for ‘ants’, referred to journalists as ‘Txakkuras’ or ‘dogs’.[24] In effect, Txinurriak was an open suggestive invitation for the assassinations of journalists, blaming the media for hiding “the reality of the suffering in the Basque country at the hands of the State”, and for their “constant harassment and destruction of the independence movement”.[25]

IS regularly accuses the media of lying about its military operations and of deceiving readers by reporting false information, and it has ordered its fighters to eliminate journalists who “damage the image of the group for the benefit of the Iraqi government”.[26] Western media are accused of failing to report IS victories and of exaggerating the strengths of IS’s enemies, such as the Peshmerga in Iraq “portrayed by the crusader media as a fierce ground force that can fend off IS (…) yet, they continue to take a beating at the hands of the mujahidin”.[27] The terrorist organisation also targets the media for reporting “lies” and “fabrications”.[28] Referring to IS’s attack on the Palestinian refugee camp of Yarmouk outside Damascus in April 2015, Dabiq stated, “following the mujahidin’s liberation of Yarmouk, the media jumped on cue and began disseminating lies against the Islamic State [29] (…) Due to the major propaganda war and the deceitful media claims, there was great fear from the Muslims of the Yarmouk camp, as the image conveyed about the Islamic State was that they love killing and slaughter and that they kill people based on suspicions”.[30]

There was ample evidence that hypothesis two could be confirmed.

Hypothesis Three

The findings revealed that this hypothesis could partly be confirmed. As an old terrorist organisation, ETA depended on the oxygen of publicity provided by the news media. Robert Clark argues that “considerable evidence” suggests that ETA planned its attacks based on their symbolic and communicative value.[31] As Paul Wilkinson explained, “the terrorists’ own organs of propaganda generally have very limited circulation”, which does not extend beyond militants and some sympathisers.[32] Consequently, the news media was crucial for ETA, illustrated by the assassination of former Spanish Prime Minister Luis Carrero Blanco in December 1973, a propaganda coup which allowed ETA to reach “the front pages of mass media around the world”.[33] In the aftermath of this attack, ETA released a statement to the media claiming responsibility and through which they “made the world aware of their fight for independence”.[34] Furthermore, ETA organised a press conference “to which they had brought a group of blindfolded journalists”.[35] The relationship between ETA and the news media was entirely symbiotic, and ETA planned its attacks based on the coverage these would attract locally, nationally, and internationally.

Unlike ETA, however, IS has practiced widespread repression against the news media and has purged territories of news media personnel. The research further suggests that IS can afford to kill journalists due to the Internet and social media. The Internet–cheap, accessible, decentralised, and mostly unregulated [36]–allows IS to spread its message and propaganda on an immediate basis and to report on its own actions.[37] The “unprecedented level of direct control” over the information it communicates “considerably extends their ability to shape how different target audiences perceive them”.[38] Whereas old terrorist organisations “had to grasp the attention of the mass media” to successfully attract press coverage, IS can “sidestep these gatekeepers and interact straightforwardly” with its audience.[39]

IS also “demonstrates a masterful understanding of effective propaganda and social media use”.[40] The vice-president and director of photography of the Associated Press, Santiago Lyon, argues that “everybody who has access to social media is in effect a publisher now. Everybody who was previously obliged to interact to some degree with the traditional media in order to reach the audiences now has their own path to do that”.[41] Unlike the ‘one to many’ model provided by traditional news media, social media allows ‘peer-to-peer’ communication, which enables IS to “reach out to their target audiences and virtually knock on their doors”.[42]

The terrorist organisation’s “highly productive media department” [43], described as “the most potent propaganda machine ever assembled by a terrorist organisation”, has been a crucial factor.[44] IS’s media branch is structured according to three levels: central media units, provincial information offices, and the broader membership/supporter base of IS.[45] Each level disseminates and promotes “the image of the organisation” [46] and shares large amounts of online material “that fit the narrative that the group wishes to convey”.[47] Moreover, IS’s supporter base–the “media mujahideen” [48]–recycles and disseminates content created by IS’s central media units, in turn expanding IS’s audience exponentially.[49] IS greatly takes advantage of and benefits from its network of online supporters, which “is larger than anything that has been seen before” from a non-state terrorist organisation.[50]

IS has been “more strategic online, demonstrates greater social media sophistication, and operates in cyberspace on a larger scale and intensity than previous terrorist groups”.[51] It is mainly through its supporter base that IS swarm-casts its propaganda and can share its message with the greatest audience.[52] The “swarm” of IS accounts on Twitter can be simply reconfigured when accounts are deleted by administrators, allowing IS to maintain its resilient online presence.[53] Gabriel Weimann further revealed that IS has made use of ‘narrowcasting’–the antonym of ‘broadcasting’, which consists of targeting the broadest possible audience with one distinctive message to all–on social media.[54] Narrowcasting enables IS to “slice the target audiences into small subpopulations” based on criteria such as demographics, gender, age, or education, and suggests that IS can tailor specific messages to distinct audiences, making different appeals to different sub-populations.[55]

Despite the means provided by the Internet and social media, the news media has not become completely redundant for IS. The terrorist organisation still needs the traditional news media in several ways.

Firstly, the terrorist organisation is exploiting local journalists in Syria and Iraq by forcing them to produce prescribed content.[56] Journalists who have refused to join IS have been executed.[57] Aside from exploiting local journalists, IS has made use of captured freelance British journalist John Cantlie, who has been held hostage since November 2012. Articles purportedly written by Cantlie were published in Dabiq, criticising Western governments [58], and describing IS’s “rapid consolidation and shrewd governance of its territories”.[59] Cantlie has also been reporting for IS from cities which the organisation has conquered, describing military advances and life within the Islamic State.[60] Until his disappearance, Cantlie was also used by IS in the ‘lend me your ears’ series, talking about IS’s expansion and seeking to show how Western media “twists and manipulates” the “truth” about life in the Islamic State.[61]

Secondly, IS is able to attract media coverage worldwide by taking and holding foreign journalists hostage, which “increases the drama”.[62] Realising that targeting journalists “nearly guarantees media coverage” [63], IS has ‘successfully’ managed to exploit the news media’s thirst for coverage that is “cinematic, emphasising dramatic scenes, stylised transitions and special effects”.[64] Regarding the hostage situation involving Japanese journalist Kenji Goto in early 2015, IS set out demands and initiated a 72-hour countdown [65], effectively luring the news media into a trap.[66] IS provided the news media with the images they are hungry for and the news media contributed to sharing IS’s message.

Thirdly, IS still orchestrates large-scale attacks to attract the attention of the traditional news media, such as the bomb onboard a Russian passenger plane, or the bomb attacks in a Shia neighbourhood in Beirut in late 2015. The aftermath of both attacks illustrated IS’s use of ‘propaganda by the deed’, reflected in IS statements claiming responsibility for both attacks and publicising its message that it is defending its ‘Caliphate’ and Sunni Muslims from the aggression of external powers.[67] It should also be emphasised that IS may be strategically claiming responsibility for attacks with which it has no direct connection, seeking additional coverage and publicity in the news media.

Lastly, IS relies on its supporters to create an online “buzz” on social media which the traditional news media will pick up and disseminate its messages further.[68] IS tailors the content of some of its videos–excluding gruesome beheadings–in order to guarantee that the news media will broadcast its videos after picking up the ‘buzz’.[69] In this way, the terrorist organisation can be sure that its videos will be shown without much censoring on television by the traditional news media, further maximising the reach of its message.[70] IS may be struggling to publicise its message online as “Western governments have successfully prodded a growing number of social media carriers to make much more serious efforts to weed out and block accounts sympathetic to IS.”[71] As a result, thousands of IS-related accounts have been deleted by Twitter while Youtube is now actively removing IS videos from its website.[72] The terrorist organisation has thus turned to the “‘dark web’, a hard-to-trace part of the Internet largely inaccessible to ordinary web browsers.”[73] This suggests that it will continue to use the traditional news media as a source of publicity.

Discussion of Findings

Killing Journalists - Rational and Strategic

Targeting journalists was a strategic choice for ETA for two reasons. Since ETA’s hoped-for changes were not implemented and the government refused to negotiate, the terrorist organisation turned to violence. By targeting journalists, ETA was also targeting the Spanish state. Journalists who supported the government and the newly-drafted Constitution became targets of the terrorist organisation. Targeted journalists were also the victims of a campaign of violence by ETA which had as its objective to force the state into submission by killing large numbers of people.

ETA did not initiate its most violent campaign against the news media before the late 1990s. The arrest of key members of ETA’s leadership in 1992 had been a devastating blow to the terrorist organisation [74], forcing it to turn to the strategy of ‘socialising the suffering’, which included targeting and killing familiar public figures in the Basque Country.[75] Influential journalists were included on ETA’s hit-list.

For ETA, targeting journalists was a rational move with strategic benefits. Journalists who openly supported the democratic transition and the Spanish Constitution were seen as opponents of Basque independence and had to be eliminated. Critical voices threatened ETA and its struggle as they undermined ETA’s image and legitimacy in the Basque Country. By targeting public figures, ETA sought to force the Spanish government into negotiations and, in turn, to influence the political process. In addition, targeting the news media was effectively “propaganda by the deed” as it sent a message to other journalists that they would be killed for opposing ETA’s struggle.

Killing journalists has also been strategic for IS since it portrays itself as a ‘state’ and as the protector of Sunni Muslims, IS strives to eliminate those who unmask the violence behind the terrorist organisation. Although IS itself shares videos of atrocities on the Internet and social media, notably to attract the attention of the news media, to intimidate its enemies, and to “provoke irrational reactions”, the organisation also broadcasts videos and images of life in the Islamic State showing, alternatively, well-stocked markets [76], playing children [77], social justice [78], or healthcare provision.[79] These are essential aspects of IS’s propaganda. These stories are rarely broadcast in the Western news media, unlike those about the terrorist organisation’s brutality. Journalists are considered legitimate targets for their negative portrayal of the terrorist organisation.

IS also wants to be seen as constantly on a war footing–expanding the borders of its ‘Caliphate’, as prescribed by its slogan “remaining and expanding”.[80] However, Charlie Winter noted that IS “depicts only the successes of its offensives, while almost entirely excluding its defensive operations”.[81] Information suggesting defeats is damaging to IS and sources of that kind of information are eliminated. Targeting news media personnel is thus a strategic choice for IS and killing journalists is also an act of “propaganda by the deed”. It sends out a message to all the news media that journalists will be killed for any coverage that is damaging to the image of IS.

Old vs. New Terrorism - A Disputable Distinction

The findings above reveal that the rationales of ETA and IS for targeting the news media are very similar. Indeed, both terrorist organisations have:

- targeted the news media for collaborating with the enemy and for negative portrayal;

- released statements which explained their justifications for their attacks on the news media, as well as publicised their struggle;

- made use of the news media for similarly strategic reasons, namely to disseminate their message to a broad audience and as propaganda by the deed; and

- aimed to attract the attention of the news media in order to spread their message.

Consequently, it can be said that there are many similarities in the relationship between the news media and old terrorist organisations, and the relationship between the news media and new terrorist organisations. In this regard, the assumption that there is a distinction between old and new terrorism must be questioned.

The third hypothesis postulated that new terrorist organisations do not need the news media to the same extent as old terrorist organisations do, due to the presences of the Internet and the social media. The traditional news media, however, is holding on to its “marriage of convenience” with terrorists.[82] Indeed, as Brigitte Nacos argues, there has been an “increased availability of the sort of oxygen Mrs. Thatcher warned of”.[83] This situation is somewhat paradoxical: new terrorism’s reliance on the news media has dwindled, but the news media continues to search for content posted by new terrorist organisations on social media and to broadcast it.

IS’s reliance on social media suggests that, for the first time in the history of terrorism, a terrorist organisation is capable of bypassing the gatekeepers of the traditional news media. IS is able to reach the audiences it wants with the message it wants and in the context it chooses. Yet, it has also become apparent that the traditional news media is not satisfied with this development, regularly picking up content posted by IS on social media in order to re-broadcast it. Not only does the traditional news media continue to provide terrorists with publicity but IS regularly and, most importantly, effortlessly manages “to hijack the news system” in the process.[84] One may therefore wonder whether the symbiotic relationship between the news media and terrorism has been changed by the rise of social media and the Internet, into one where the news media needs terrorism more than terrorism needs the news media.

Conclusion

The thesis’ findings summarised in this Research Note make clear that ETA and IS share similar rationales for targeting the news media. Both organisations considered that the news media was actively collaborating with their enemies, either in the form of spying or as accomplices of the oppression they faced. Both ETA and IS killed journalists for spreading “lies” and “calumnies” and both targeted the news media for misrepresenting their terrorist organisation, as well as for critical comments or ‘false’ information regarding their struggle, tactics, or violent campaigns.

These findings suggest that old and new terrorist organisations target journalists for similar reasons, questioning the validity of distinguishing between ‘old’ and ‘new’ terrorism. With regards to targeting the news media, such a distinction does not make sense as both ETA and IS used identical rhetoric to justify killing journalists. More research including additional terrorist organisations would need to be conducted to further substantiate these findings and to suggest whether or not the findings can be generalised.

The research summarized here also revealed that the traditional news media has not become completely redundant for IS. Not only does IS exploit local and foreign journalists to work for its media department, but it appears that ‘propaganda by the deed’ remains a key aspect of IS’s strategy. The terrorist organisation still needs the news media to publicise its message and IS still orchestrates attacks or hostage situations to attract the attention of the news media and by providing coverage that can be sold to anxious audiences. IS has not yet completely relinquished its symbiotic relationship with the news media.

The findings call for further research on the changing “symbiotic” relationship between the news media and terrorism. It was argued that the news media today may need terrorism more than terrorism needs the news media; consequently, research should address whether this relationship can indeed still be characterised as a symbiosis. As the findings are limited to two case studies, additional research would need to be conducted to determine whether the findings presented in this Research Note can be generalised.

About the Author: François Lopez received his Master’s degree from the Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs of Leiden University’s The Hague Campus, concentrating on Crisis and Security Management. His previous research had focused on international security issues and lone wolf terrorism in France.

Notes

[1] Thatcher, M. (1985) Speech to American Bar Association. Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106096 .

[2] Abraham Miller in, Tuman, J. (2009) Communicating Terror: The Rhetorical Dimensions of Terrorism. SAGE Publications, 2nd Edition, p.163.

[3] Schmid, A., De Graaf, J. (1982) Violence as communication: insurgent terrorism and the Western news media. SAGE, p.13 & Weimann, G. (2005) The Theater of Terror, Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 9:3-4, p.383.

[4] Laqueur, W. cited in Schlesinger, P. (1981) Terrorism, the media, and the liberal-democratic state: A Critique of the Orthodoxy. Social Research 48, p.85.

[5] Nacos, B. (2007) Mass-Mediated Terrorism: The central role of the media in terrorism and counterterrorism. Lanham, Md. : Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, p.37.

[6] Surette, R., Hansen, K., Noble, G. (2009) Measuring media oriented terrorism. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37, 4, p.367.

[7] Graph created by the author of this Research Note based on Reporters Without Borders (2015) Journalists killed. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from https://en.rsf.org/press-freedom-barometer-journalists-killed.html & Reporters Without Borders (2015) Round-up of journalists killed worldwide 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016, from http://en.rsf.org/IMG/pdf/rsf_2015-part_2-en.pdf, p.67.

[8] Global Terrorism Database (2015) Incidents Over Time targeting journalists & media. University of Maryland. Retrieved 25 October 2015, from http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/search/Results.aspx?start_yearonly=&end_yearonly=&start_year=&start_month=&start_day=&end_year=&end_month=&end_day=&asmSelect0=&asmSelect1=&target=10&dtp2=all&success=yes&casualties_type=b&casualties_max= .

[9] Firstly, whereas old terrorist organisations were mainly nationalist and secular in their goals, new terrorists are religiously motivated. Secondly, old terrorism was intrinsically territorial and focused on a ‘homeland’, while new terrorism is de-territorialised and has a global outlook. Thirdly, the use of violence by old terrorist organisations has been described as more targeted and proportionate, in contrast to new terrorist organisations’ reliance on indiscriminate violence. Lastly, old terrorist organisations were characterised by a hierarchy in their leadership with a clearly defined command and control structure. New terrorist groups, however, are composed of various cells and networks, and are said to lack an identifiable hierarchy. – Cf. Crenshaw, M. (2007) The Debate over “New” vs. “Old” Terrorism. American Political Science Association. Retrieved 1 December 2015, from http://www.start.umd.edu/sites/default/files/files/publications/New_vs_Old_Terrorism.pdf, p.7 & Neumann, P. (2009) Old and New Terrorism. Social Europe. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://www.socialeurope.eu/2009/08/old-and-new-terrorism/ & Spencer, A. (2006) Questioning the Concept of “New Terrorism”. The Journal of Peace, Conflict & Development, Issue 8, p.7-9

[10] Crenshaw, M. (1987) Theories of terrorism: Instrumental and organizational approaches. Journal of Strategic Studies, Volume 10, Issue 4, p.13.

[11] McAllister, B., Schmid, A.P.; in Alex P. Schmid (Ed.) (2011) The Routledge Handbook of Terrorism Research. London & New York: Routledge, p. 246.

[12] Garrison, A. (2004) Defining terrorism: philosophy of the bomb, propaganda by deed and change through fear and violence, Criminal Justice Studies, 17:3, p.268 & Matusitz, J. (2012) Terrorism and Communication: A Critical Introduction. SAGE Publications, p.39 & Schmid, A. (2005) Terrorism as Psychological Warfare, Democracy and Security, 1:2, p.139.

[13] Observatorio da Imprensa (n.d.) PAÍS BASCO: A imprensa como alvo do terror. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://www.observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/artigos/mo270320021.htm.

[14] Clark, R. (1984) The Basque Insurgents: ETA, 1952-1980. The University of Wisconsin Press, p.64.

[15] El Mundo (2006) Afirmaciones de ETA sobre los periodistas y los medios de comunicación. Retrieved 4 November 2015, from http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2006/02/12/espana/1139718186.html.

[16] ABC (2001) ETA dice que Interior usa los medios de comunicación como ‘arma de guerra’. Retrieved 4 November 2015, from http://www.abc.es/hemeroteca/historico-22-03-2001/abc/Nacional/eta-dice-que-interior-usa-los-medios-de-comunicacion-como-arma-de-guerra_19348.html .

[17] The Clarion Project (2014) Dabiq Issue 9: They plot and Allah plots. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://media.clarionproject.org/files/islamic-state/isis-isil-islamic-state-magazine-issue%2B9-they-plot-and-allah-plots-sex-slavery.pdf, p.70.

[18] The Clarion Project (2014) Dabiq Issue 5: Remaining and Expanding. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://media.clarionproject.org/files/islamic-state/isis-isil-islamic-state-magazine-issue-5-remaining-and-expanding.pdf, p.3.

[19] The Clarion Project (2014) Dabiq Issue 11: From the Battle of Al-Ahzab to the War of Coalitions. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://www.clarionproject.org/docs/Issue%2011%20-%20From%20the%20battle%20of%20Al-Ahzab%20to%20the%20war%20of%20coalitions.pdf, p.5.

[20] Reporters Without Borders (2015) Mosul Journalists are dying amid resounding silence. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://fr.rsf.org/IMG/pdf/iraq_mosul_report_.pdf, p.3-6 & Nazish, K. (2015) Life under Islamic State rule in Mosul one of constant fear. USA Today. Retrieved 16 November 2015, from http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2015/10/25/life-under-islamic-state-rule-mosul-one-constant-fear/74383082/& Rudaw (2015) Journalist tried and executed same day by ISIS in Mosul. Retrieved 16 November 2015, from http://rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/160820155 & Varghese, J. (2015) Iraq: Isis Executes Woman Journalist in Mosul for Spying. International Business Times. Retrieved 16 November 2015, from http://www.ibtimes.co.in/iraq-isis-kills-woman-journalist-mosul-spying-638445.

[21] International Media Support (2014) Local media both victim and perpetrator in Iraq crisis. Retrieved 16 November 2015, from http://www.mediasupport.org/local-media-both-victim-and-perpetrator-in-iraq-crisis/.

[22] Landaburu, A. (2008) ETA mató al mensajero. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://elpais.com/diario/2008/06/28/paisvasco/1214682000_850215.html.

[23] The KAS was a committee of strategic coordination involving radical nationalist movements of the Basque Country, of which ETA was a member. Fernandez-Soldevilla, G. (2014) Los orígenes de KAS, la Koordinadora Abertzale Sozialista. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from https://gaizkafernandez.wordpress.com/2014/08/13/los-origenes-de-kas-la-koordinadora-abertzale-sozialista/.

[24] Barberia, J.L. (1995) Un documento interno de KAS abre la puerta a los atentados de ETA contra periodistas. El Pais. http://elpais.com/diario/1995/01/27/espana/791161223_850215.html.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Reporters Sans Frontières (2015) Les zones contrôlées par le groupe EI, véritables ‘trous noirs’ de l’information. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://fr.rsf.org/irak-les-zones-controlees-par-le-groupe-23-10-2014,47146.html.

[27] The Clarion Project (2014) Dabiq Issue 6: Al-Qa’idah of Waziristan: A Testimony From Within. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://media.clarionproject.org/files/islamic-state/isis-isil-islamic-state-magazine-issue-6-al-qaeda-of-waziristan.pdf, p.32 & The Clarion Project (2014) Dabiq Issue 10: The Laws of All or the Laws of Men. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://www.clarionproject.org/docs/Issue%2010%20-%20The%20Laws%20of%20Allah%20or%20the%20Laws%20of%20Men.pdf, p.32.

[28] The Clarion Project (2014) Dabiq Issue 9: They plot and Allah plots. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://media.clarionproject.org/files/islamic-state/isis-isil-islamic-state-magazine-issue%2B9-they-plot-and-allah-plots-sex-slavery.pdf, p.70.

[29] Ibid., p.35.

[30] Ibid., p.70.

[31] Clark, R. (1984) The Basque Insurgents: ETA, 1952-1980. The University of Wisconsin Press, p.123.

[32] Wilkinson, P. (1997) The media and terrorism: A reassessment, Terrorism and Political Violence, 9:2, p.54.

[33] Olmeda, J. (2011) ETA Before and After the Carrero Assassination. Strategic Insights, Vol. 10, Issue 2, p.8.

[34] Bieter, M. (2013) The Rise and Fall of ETA. The Blue Review. Retrieved 11 November 2015, from https://thebluereview.org/rise-fall-eta/.

[35] Clark, R. (1984) The Basque Insurgents: ETA, 1952-1980. The University of Wisconsin Press, p.77.

[36] Nacos, B. (2007) Mass-Mediated Terrorism: The central role of the media in terrorism and counterterrorism.

Lanham : Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, p.115.

[37] Ibid., p.114.

[38] Conway, M. (2006) Terrorism and the Internet: New Media–New Threat? Parliamentary Affairs, Vol.59, 2, p.284.

[39] Matusitz, J. (2012) Terrorism and Communication: A Critical Introduction. SAGE Publications., p.345.

[40] Vitale, H-M., Keagle, J.M. (2014) A Time to Tweet, as Well as a Time to Kill: ISIS’s Projection of Power in Iraq and Syria. Institute for National Strategic Studies, 77, p.1.

[41] Lyon, S. (2015) Emphasis Added: The Media and The Islamic State. Vice News. Retrieved 17 November 2015,

from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Labn-IIwFhs.

[42] Weimann, G. (2014) New Terrorism and New Media. Wilson Centre, Research Series Vol. 2, p.3.

[43] Barrett, R. (2014) The Islamic State. The Soufan Group. Retrieved 17 November 2015, from http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/TSG-The-Islamic-State-Nov14.pdf, p.53.

[44] Miller, G., Mekhennet, S. (2015) Inside the surreal world of the Islamic State’s propaganda machine. The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 November 2015, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/inside-the-islamic-states-propaganda-machine/2015/11/20/051e997a-8ce6-11e5-acff-673ae92ddd2b_story.html.

[45] Ingram, H. (2015): The strategic logic of Islamic State information operations, Australian Journal of International Affairs, DOI: 10.1080/10357718.2015.1059799, p.6.

[46] Barrett, R. (2014) The Islamic State. The Soufan Group. Retrieved 17 November 2015, from http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/TSG-The-Islamic-State-Nov14.pdf, p.53.

[47] Al-Ubaydi, M. et.al. (2014) The Group That Calls Itself a State: Understanding the Evolution and Challenges of the Islamic State. The Combating Terrorism Centre at West Point. Retrieved 17 November 2015, from https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-group-that-calls-itself-a-state-understanding-the-evolution-and-challenges-of-the-islamic-state, p.47.

[48] Fisher, A. (2015) Swarmcast: How Jihadist Networks Maintain a Persistent Online Presence. Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol.9, Issue 3, p. 2.

[49] Al-Ubaydi, M. et.al. (2014) The Group That Calls Itself a State: Understanding the Evolution and Challenges of the Islamic State. The Combating Terrorism Centre at West Point. Retrieved 17 November 2015, from https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-group-that-calls-itself-a-state-understanding-the-evolution-and-challenges-of-the-islamic-state, p.50.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Fidler, D. (2015) Countering Islamic State Exploitation of the Internet. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 17 November 2015, from http://www.cfr.org/cybersecurity/countering-islamic-state-exploitation-internet/p36644.

[52] Barrett, R. (2014) The Islamic State. The Soufan Group. Retrieved 17 November 2015, from http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/TSG-The-Islamic-State-Nov14.pdf, p.51.

[53] Fisher, A., Prucha, N. (2014) ISIS Is Winning the Online Jihad Against the West. The Daily Beast. Retrieved 17 November 2015, from http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/10/01/isis-is-winning-the-online-jihad-against-the-west.html .

[54] Weimann, G. (2015) Terrorism in Cyberspace: The Next Generation. Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 December 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uwxY99D1tMg .

[55] Weimann, G. (2015) Terrorism in Cyberspace: The Dark Future? Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 December 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q8dEB_CeJ-8.

[56] Hatem, O. (2015) In Iraq, Islamic State Exacts Heavy Toll on Journalists and Their Families. MediaShift. Retrieved 19 November 2015, from http://mediashift.org/2015/04/in-iraq-islamic-state-exacts-heavy-toll-on-journalists-and-their-families/.

[57] Hetzer, R. (2015) 2015 threatens to end as deadliest year on record. International Press Institute. Retrieved 26 October 2015, from http://www.freemedia.at/newssview/article/2015-threatens-to-end-as-deadliest-year-on-record.html .

[58] The Clarion Project (2014) Dabiq Issue 7: From Hypocrisy to Apostasy. Retrieved 19 November 2015, from http://media.clarionproject.org/files/islamic-state/islamic-state-dabiq-magazine-issue-7-from-hypocrisy-to-apostasy.pdf, p.76.

[59] The Clarion Project (2014) Dabiq Issue 12: Just Terror. Retrieved 19 November 2015, from http://www.clarionproject.org/docs/islamic-state-isis-isil-dabiq-magazine-issue-12-just-terror.pdf, p.50.

[60] Elgot, J. (2015) John Cantlie, Islamic State Hostage Journalist, Says New Video Is ‘Last In Series’. Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 November 2015, from http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2015/02/09/john- cantlie-video_n_6645876.html.

[61] Times of Lebanon (2014) John Cantlie Lend Me Your Ears. Youtube. Retrieved 19 November 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vcew3qmidRI .

[62] Jenkins, B. cited in Weimann, G. (2015) From Theaters to Cyberspace: Mass-Mediated Terrorism. Worldviews for the 21st Century, Vol.13, 1, p.4.

[63] Surette, R., Hansen, K., Noble, G. (2009) Measuring media oriented terrorism. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37, 4, p.367.

[64] Miller, G., Mekhennet, S. (2015) Inside the surreal world of the Islamic State’s propaganda machine. The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 November 2015, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/inside-the-islamic-states-propaganda-machine/2015/11/20/051e997a-8ce6-11e5-acff-673ae92ddd2b_story.html .

[65] Saul, H. (2015) Isis-linked ‘countdown clock’ reaches zero as 72-hour deadline to save hostages expires. The Independent. Retrieved 19 November 2015, from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/isis-militants-post-countdown-has-begun-after-72-hour-deadline-for-hostages-expired-9997505.html .

[66] Ingram, H. (2015): The strategic logic of Islamic State information operations, Australian Journal of International Affairs, DOI: 10.1080/10357718.2015.1059799, p.18.

[67] Elgot, J., Johnston, C. (2015) Russian plane crash: investigation into cause begins – as it happened. The Guardian. Retrieved 5 December 2015, from http://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2015/oct/31/russian-passenger-plane-crashes-in-egypts-sinai-live & Loveluck, L. (2015) Isil claims responsibility in deadliest attack in Beirut since end of civil war kills dozens. The Telegraph. Retrieved 5 December 2015, from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/lebanon/11992262/Isil-suspected-in-deadliest-attack-in-Beirut-since-end-of-civil-war-kills-dozens.html .

[68] Seib, P., Janbek, D. (2009) Global Terrorism and New Media: The Post-Al Qaeda Generation. Routledge, p.59.

[69] Ingram, H. (2014) Three Traits of the Islamic State’s Information Warfare. The RUSI Journal, 159:6, p.5.

[70] Ibid.

[71] The Economist (2015, December) Unfriended. Vol.417, Number 8968, p.32.

[72] Ibid.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Whitfield, T. (2014) Endgame for ETA: Elusive Peace in the Basque Country. Hurst & Company, London, p.74.

[75] Ibid., p.84.

[76] Winter, C. (2015) Documenting the Virtual Caliphate. Quilliam Foundation. Retrieved 25 October 2015, from http://www.quilliamfoundation.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/FINAL-documenting-the-virtual-caliphate.pdf, p.33.

[77] Ibid., p.32.

[78] Ibid., p.34.

[79] Ibid., p.35.

[80] Barrett, R. (2014) The Islamic State. The Soufan Group. Retrieved 17 November 2015, from http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/TSG-The-Islamic-State-Nov14.pdf, p.23.

[81] McAllister, B., Schmid, A. P., in Alex P. Schmid (Ed.) (2011) The Routledge Handbook of Terrorism Research. London & New York: Routledge, p.246.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Nacos, B. (2007) Mass-Mediated Terrorism: The central role of the media in terrorism and counterterrorism. Lanham, Md.: Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, p.36.

[84] McAllister, B., Schmid, A.P., in Alex P. Schmid (Ed.),(2011) The Routledge Handbook of Terrorism Research. London & New York: Routledge, p. 247.